HISTORY 0F JUJITSU

Self-defense being natural to

everybody, there is perhaps no country

where the art of fighting unarmed, whatever its form, is unknown, but

perhaps in no country has the art made such remarkable progress as in

Japan. In the feudal days of this country there existed various schools

of such art, being known by the different names of jujitsu, taijitsu,

yawara, wajitsu, toride, kogusoku, kempo, hakuda, kumiuchi, shukaku,

judo, etc. They are so intermingled with one another that any correct

discrimination between them is almost impossible; for instance, one

being nominally different from but virtually analogous to another,

while the other varies from its namesake as regards its essential

points. We may, however, state that, of these, toride and kogusoku are

intended for the arrest of persons, while jujitsu and judo make it a

specialty either to floor or kill one's opponent and kempo and hakuda

to kick and strike. Generally speaking, they may all be described as

the art either of fighting with an armed or unarmed enemy, oneself

utterly unarmed, or of engaging by means of a small weapon an enemy

armed with a large one.

The various schools mentioned

above have had their own foremost

champions who, endowed with high intellectual powers, have assiduously

devolved their whole life to the study of their beloved art. And they

were duly rewarded. Not only have they succeeded, with wonderful knack

or by means of real strength, in mastering the art of gaining a victory

over an enemy, but they have. contributed to the unequaled development

of the art by discovering many fundamental rules bearing on manifold

manoeuvres against one's antagonist, delicate movements arising from

harmonious muscular action, display of pluck, training of intellectual

faculties, etc.

Opinions differ as to the

origin of the art. One traces it to Chin

Gempin, a naturalized Chinese, of whom mention is made in the following

paragraph. Another attributes it to Shirobei Akiyama, a physician at

Nagasaki, who is stated to have learned three tricks of hakuda in

China. A third, on the other hand, claims the art to be the production

of pure Japanese ingenuity.

To state more in detail, Chin

Gempin was naturalized as a Japanese

subject in 1659 and died in 1671. While sojourning at the Kokushoji

temple at Azabu, Tokyo (then Yedo), he, it is stated, taught three

tricks of jujitsu to three ronin (samurai discharged from their lord's

service). These ronin were Shichiroyemon Fukuno, Yojiyemon Miura and

Jirozayemon Isogai, and after much study, they each founded their own

schools of jujitsu. It is beyond doubt that what was learned by them

consisted of three kinds of atewaza (that is to say, striking the vital

and vulnerable parts of the body) of the Chinese kempo (pugilism). We

cannot, therefore, arrive at the hasty conclusion that Chin is the

founder of jujitsu in this country, though it must be stated to his

credit that his teaching gave an undoubted impulse to the development

of jujitsu.

The second of the-three views,

conferring upon Shirobei Akiyama the

honour of being the pioneer of jujitsu in Japan, is maintained by one

of the Shinyo schools and is not supported by any other schools. This

theory, like the preceding one, can scarcely hold water, since kempo

and hakuda of China, the latter of which arts Akiyama learnt in that

country, were no doubt confined solely to kicking and striking, and it

is highly improbable that jujitsu, the art of throwing and killing, was

originated by him.

What then, you may ask, has

given rise to such incredible

traditions? It is possible that the authors of the two views expressed

above found it expedient to give to the Chinese the credit of being the

founder of jujitsu in this country, for by this action they might gain

the greater confidence of the public than declaring themselves as

originators of the art — a consideration quite natural to exponents of

new ideas and things. This supposition is in a way explained by the

fact that in former days the Chinese were held in high esteem in Japan,

as were Westerners later, so high indeed that our forefathers often

accepted with undue credulity anything attributed to Chinese school of

thought.

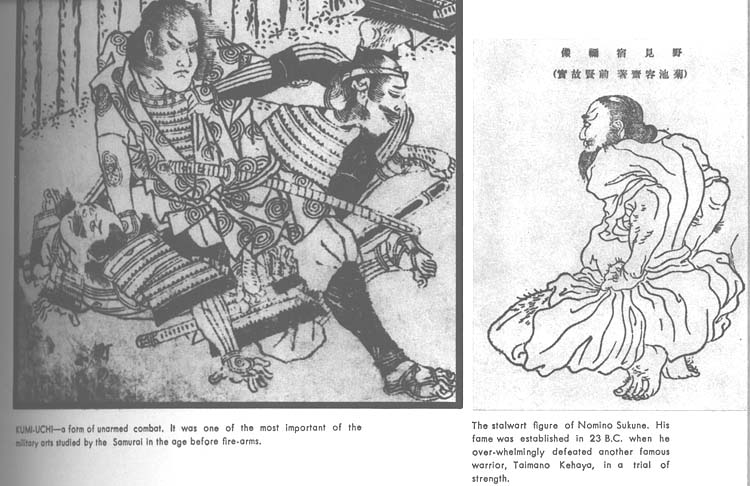

What may be considered as a

strong proof against the above

mentioned views is that both yawara and toride are referred to in a

book styled "Kuyamigusa " (My Confessions) which was published in 1647,

twelve years prior to the immigration of Chin Gempin. Moreover, the

term kumiuchi is often found in still older books. These records afford

ground for believing that jujitsu prevailed in Japan at a much earlier

period. Further, the Takenouchi school, which is acknowledged by the

majority of jujitsu professors to be the oldest of the kind, was

founded in 1532 by Hisamori Takenouchi. It is therefore indisputable

that that school was in existence long before Chin Gempin ever set foot

on this land.

All these considerations go far

towards confirming the claim of the

third view, that jujitsu is indigenous and not foreign. It is true that

the terms jujitsu, yawara, etc., are quite modern, but the art, in its

initial stages, can be traced as far back as 24 B. C. In that year, so

the record goes, Emperor Suinin ordered two strong men, Nomi-no-Sukune

and Taima-no-Kuehaya, to wrestle in his presence. After fighting, which

consisted mainly of kicking, the former gained the ascendancy and

finally broke the ribs of his opponent. Elated by his success, Nomi

went the length of trampling upon and breaking the loins (ouch! DH) of

his vanquished competitor, which ended fatally to the latter. This

record is generally accepted as showing the origin of wrestling in this

country. Considering, however, the fact that Kuehaya was kicked to

death, it seems that the contest partook more of the nature of jujitsu

than that of wrestling.

In those ancient days there

existed of course no distinction

between wrestling and jujitsu and as the latter name was then quite

unknown it may be that the tragic event was recognized in a general way

as the origin of wrestling. Be that as it may, there developed in the

Middle Ages, when the country was the scene of horrible wars and

strifes, the art of kumiuchi which was a kind of wrestling applied to

encounters on the battle-field. After many year's development the art

advanced to such a degree that even the weak often gained a glorious

victory over a strong foe, thus encouraging every aspiring warrior to

train himself thoroughly in it. As years went on the art made a

two-fold development. It gave rise, on the one hand, to wrestling,

properly so called, which, as it developed, lost its practical use,

and, on the other, to jujitsu which has since attained almost

unprecedented perfection. It need scarcely be said that jujitsu serves

one as a valuable aid in emergencies.